If your doctor or dietitian has recently mentioned FODMAPs, you might be wondering what on earth they’re talking about. The term sounds intimidating—like something you’d need a science degree to understand—but the concept is actually pretty straightforward once you strip away the jargon.

Let’s break down what FODMAPs are, why they cause digestive problems for some people, and what you can actually do about it.

What Are FODMAPs, Really?

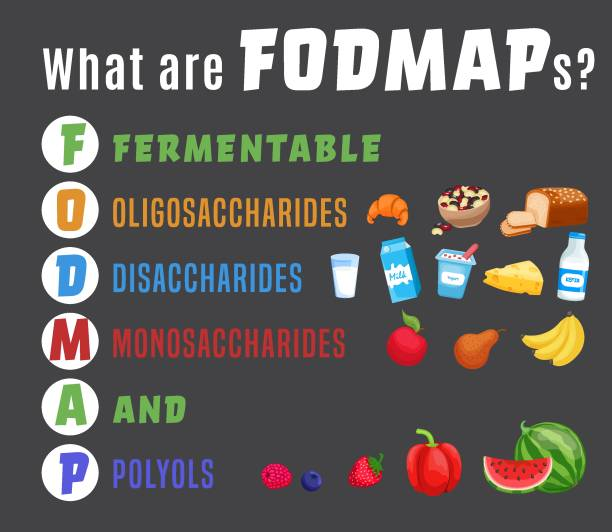

FODMAP is an acronym that stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. Yes, that’s a mouthful. But here’s the simple version: FODMAPs are types of carbohydrates (sugars and fibers) that some people’s digestive systems struggle to break down and absorb.

These aren’t weird chemical additives or artificial ingredients. FODMAPs are found naturally in many common, healthy foods—things like wheat, dairy products, onions, apples, and beans. For most people, these foods cause no issues whatsoever. But for people with sensitive digestive systems, particularly those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), FODMAPs can trigger uncomfortable symptoms.

Here’s what happens: When you eat high-FODMAP foods, your small intestine is supposed to break them down and absorb them. But if you have FODMAP intolerance, these carbohydrates don’t get fully absorbed. Instead, they travel to your large intestine where bacteria ferment them (hence the “F” in FODMAP—fermentable). This fermentation process produces gas. At the same time, FODMAPs draw water into your intestines.

The result? Bloating, gas, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, or a combination of these symptoms. It’s not an allergy or a gluten issue (though the symptoms can overlap)—it’s simply a matter of your digestive system being sensitive to the way these particular carbohydrates behave in your gut.

Breaking Down the FODMAP Categories

Let’s look at each type of FODMAP in plain terms:

Oligosaccharides are chains of sugar molecules linked together. The two main types that cause problems are fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS). Fructans are found in wheat, rye, onions, garlic, and some vegetables like broccoli. GOS shows up primarily in legumes—beans, lentils, and chickpeas. Your body doesn’t produce the enzymes needed to break these down efficiently, so they pass through to your large intestine intact.

Disaccharides in the FODMAP world specifically refers to lactose—the sugar in milk and dairy products. Lactose requires an enzyme called lactase to be digested. Many people produce less lactase as they get older, which is why dairy can become harder to digest over time. This is different from a milk allergy, which involves the immune system. Lactose intolerance is simply a lack of the right enzyme to process milk sugar.

Monosaccharides refers to excess fructose—a simple sugar found in fruits, honey, and some sweeteners. The key word here is “excess.” When a food has more fructose than glucose (another sugar), your intestines can struggle to absorb it. This is why some fruits like apples and pears cause problems, while others like bananas and oranges are generally fine. The ratio matters.

Polyols are sugar alcohols—sweeteners that occur naturally in some fruits and vegetables (like stone fruits and mushrooms) and are also added to sugar-free products. Names like sorbitol, mannitol, and xylitol fall into this category. These molecules are large and difficult for your body to absorb, which is why sugar-free gum often comes with a warning about potential digestive effects.

Why Some People React and Others Don’t

Not everyone who eats high-FODMAP foods experiences problems. In fact, most people don’t. So why do some people react?

The exact mechanisms aren’t completely understood, but research suggests that people with IBS have more sensitive intestines that react more strongly to the stretching and distension caused by gas and water accumulation. Their gut nerves send stronger pain signals in response to normal digestive processes.

Additionally, some people may have imbalances in their gut bacteria, changes in gut motility (how quickly food moves through the digestive system), or heightened stress responses that make them more susceptible to FODMAP-related symptoms.

It’s worth noting that FODMAP intolerance isn’t permanent or fixed. Your tolerance can change based on stress levels, overall gut health, what else you’ve eaten that day, and even where you are in your menstrual cycle. This variability is part of what makes managing it tricky.

The Low-FODMAP Diet Approach

The standard way to handle FODMAP intolerance is through a structured dietary approach called the low-FODMAP diet. This isn’t meant to be a permanent elimination diet—that’s a common misconception. Instead, it’s a three-phase process designed to identify your specific triggers.

Phase 1: Elimination involves strictly avoiding high-FODMAP foods for 2-6 weeks. This gives your digestive system a break and allows symptoms to calm down. During this time, you’re eating low-FODMAP alternatives—things like rice instead of wheat, lactose-free milk instead of regular milk, green beans instead of onions.

Phase 2: Reintroduction is where you systematically test individual high-FODMAP foods to see which ones you actually react to. You might discover that you can handle lactose just fine but garlic destroys you. Or that small amounts of wheat are okay but beans are not. This phase requires patience and careful observation, but it’s crucial because it prevents you from unnecessarily restricting foods you can actually tolerate.

Phase 3: Personalization involves creating a long-term eating pattern based on what you learned. You continue eating the foods you tolerate well and limit only the specific FODMAPs that cause you problems. Most people find they can reintroduce many foods in small to moderate amounts.

The entire process typically takes 2-3 months, and it’s much easier with guidance from a registered dietitian who specializes in digestive health. They can help you navigate the confusing aspects, ensure you’re getting proper nutrition, and interpret your results accurately.

Beyond Diet: Other Management Tools

While dietary changes are the foundation of managing FODMAP intolerance, they’re not the only tool available.

Digestive enzyme supplements can help break down specific FODMAPs. Lactase enzymes help with dairy, alpha-galactosidase helps with oligosaccharides from beans and vegetables, and xylose isomerase helps with excess fructose. These supplements don’t work for everyone or for all FODMAPs, but they can provide flexibility when used strategically (you can learn more here).

Portion control matters significantly. Many people can tolerate small amounts of high-FODMAP foods without symptoms. A few pieces of apple might be fine, while a whole apple triggers problems. Learning your threshold for different foods gives you more flexibility than complete avoidance.

Stress management plays a bigger role than many people realize. Stress directly impacts gut function and can lower your tolerance threshold. Even if you can’t eliminate stress (who can?), techniques like regular exercise, adequate sleep, and mindfulness practices can improve digestive symptoms.

Gut-directed hypnotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have shown effectiveness for IBS symptoms in clinical studies. These approaches work on the gut-brain connection, potentially reducing visceral hypersensitivity (the tendency to feel pain more intensely in the digestive tract).

Probiotics are controversial in the FODMAP world. Some strains may help, others may worsen symptoms. If you’re interested in trying probiotics, look for low-FODMAP options and introduce them carefully.

Living with FODMAP Intolerance

The good news is that FODMAP intolerance is highly manageable once you understand your personal triggers. Most people don’t need to follow a strict low-FODMAP diet forever. After the initial elimination and reintroduction phases, many find they can eat a reasonably varied diet by avoiding their worst triggers and managing portions of other foods.

It does require more awareness around food choices. You’ll probably spend more time reading ingredient labels, asking questions at restaurants, and planning ahead when traveling. Social situations can be challenging when you’re first figuring things out, but they become easier as you develop strategies and learn what works for your body.

The key is approaching it as a learning process rather than a life sentence of restriction. Every person’s FODMAP tolerance is unique, and discovering your individual pattern gives you control over your symptoms instead of feeling controlled by them.

Getting Started

If you suspect FODMAPs might be causing your digestive issues, the first step is talking with your doctor to rule out other conditions. Celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and other digestive disorders can have similar symptoms but require different treatment approaches.

Once other conditions are ruled out, working with a FODMAP-trained dietitian makes the process much smoother. They can provide meal plans, help you interpret symptoms during reintroduction, and ensure you’re not unnecessarily restricting your diet.

Understanding FODMAPs doesn’t require a science degree—just patience and willingness to pay attention to how your body responds to different foods. With the right approach, most people with FODMAP intolerance can significantly reduce their symptoms and get back to enjoying food without constant digestive distress.